Here are a few things you should know about Moldova as a wine country. First, wine is constitutionally recognized as food. In March 2017, the Parliament of Moldova declared wine as a food product. The new law allows wine to be sold in shops after 22:00; advertising wine products on the mass media is also permitted. Second, there’s a public holiday dedicated to wine. Along with the declared holiday comes an annual national wine celebration held in the capital city Chișinău on the first weekend of October. Third, it is home to the largest wine cellar and the largest wine collection in the world. The state-owned Mileștii Mici winery contains around 2,000,000 bottles of wine and boasts a 200 kilometer-long cellar, of which 55 kilometers are currently in use. Fourth, Moldova has the greatest density of vineyards in the world: 3.8% of the country’s territory and 7% of the arable land. Fifth, the wine sector accounts for nearly 10% of Moldova’s labor force.

Wedged between Romania and Ukraine, Moldova is a landlocked country located in the Black Sea Basin—an area where the history of wine dates back thousands of years and a few Black Sea countries claiming to be the birthplace of wine. Together with Georgia, Moldova was one of the two most productive wine states in the Soviet Union. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and Moldova’s independence, Moldova continued to supply inexpensive bulk wine to Russia. To cater to the Russian market, besides the focus on quantity over quality, Moldova’s wine production was dominated by semi-dry and semi-sweet wines, which were favored by the Russians.

The customary setup was disturbed in 2006—and again in 2013—when Russia applied an embargo on Moldovan wine. In 2006, when Russia accounted for over 80% of Moldovan wine exports, the embargo pushed Moldova into a deep recession.

What does one do when one has its trust broken and feels betrayed? One turns away, runs as far away as possible, and tries to never look back.

After the 2013 embargo, in a political piece for The New York Times, American journalist Nicholas Kristof wrote, “If there were an Olympic competition for bravest country in the world, the gold medal might well go to Moldova.”

Moldova adopted an international approach in order to find new export markets and sustainable growth. A key challenge that arose from this shift was how to satisfy the new customers and investors who had different psychographics and different taste preferences from the Russians. Tested, Moldovan wine producers started their march from quantity to quality and from bulk to bottle.

We had our first taste of Moldovan wine when we judged at the International Wine Competition Bucharest (IWCB) 2018 and scored several of them well between 85 and 94 points. So when we received our invitation to visit the Moldovan wine regions, we accepted it with enthusiasm and high expectations. The week-long trip offered us a comprehensive overview of the three wine regions of Moldova, along with some penetrating observations of the past, present, and future of Moldovan wine.

During the week, we tasted more than 150 wines from over 20 producers. We met with enologists from some of the biggest wineries in Moldova, small-scale producers, winemakers who have just started commercializing their wines, vine breeders, wine bar owners, representatives from the tourism board, and several other key players in the wine and tourism industries. Our expectations were exceeded by the quality of Moldovan wines, the above-mentioned exponents, and the human spirit that inevitably upholds the collective vision of the Moldovan wine world.

Moldova has 112,000 hectares of vineyards planted with over 50 types of wine grape varieties, 10% of which are local types, 17% are Caucasian, and 73% are European.

The country sits on similar latitudes to the classic wine regions of the world, like Bordeaux and Piedmont. Coupled with low hills, sun-soaked plains, flowing rivers, and moderately-continental climate with influences from the Black Sea, Moldova offers suitable conditions for cultivating high-quality wine grapes.

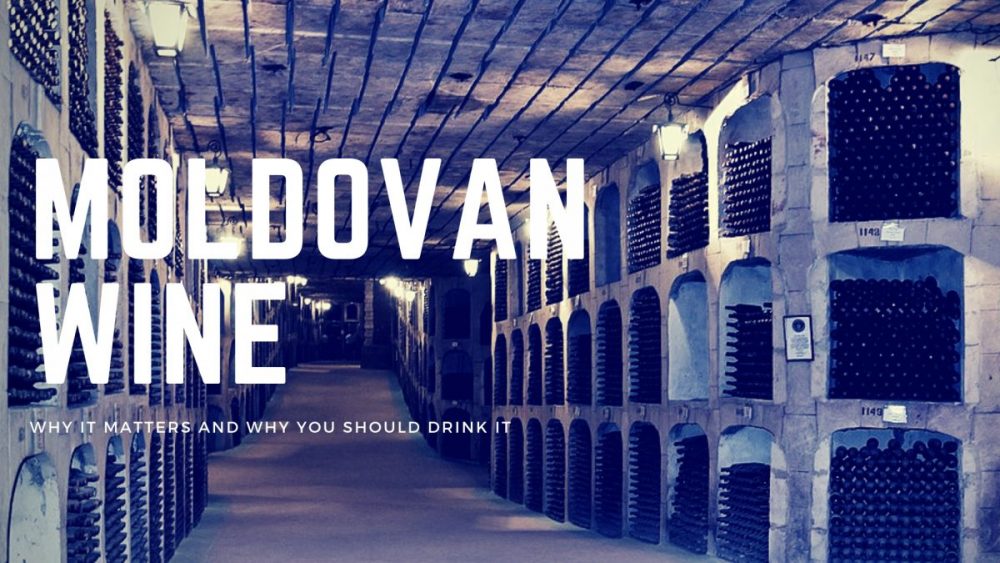

There are three Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) Moldovan wine regions: Codru (central Modolva), Valul lui Traian (southwest Moldova), and Ștefan Vodă (southeast Moldova). The latter two are more renowned for reds because of the southerly location and slightly warmer climate. However, there are some age-worthy, cool-climate reds from the Codru region as well. On the other end of the spectrum, Moldova has many aromatic white grapes and the wines made from those grapes tend to be fresh and floral. Other styles made in Moldova include sparkling and sweet. The latter includes icewines, which can be outstanding and some of the best in the world—especially if one considers their price-quality ratios. The former consists of generally simple wines with less than a handful of exceptions; however, Moldovan sparkling wine, in fact, has a history dating back to the 1950s as the deep limestones quarries at Cricova Winery (second biggest wine cellar in the world, with 120 kilometers underground tunnel that goes as deep as 100 meters below ground) and Mileștii Mici Winery proved ideal for aging and storing traditional-method sparkling wine.

The Moldovan wine industry is largely reliant on international grapes. While the first impression may appear weak on this account, there are several commendable Bordeaux-style blends that rank high for being value for money and are likely to satisfy discerning drinkers on a weekday business dinner. Most of the international red grapes—such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Malbec, Merlot, and Syrah—are also ideal for blending with local varieties. As one might expect, Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc are omnipresent white varieties and can also be found in Moldova.

Recommended white wines: Asconi Sol Negre Chardonnay 2015, Cricova Blanc de Noirs Extra Brut NV, Château Vartely Taraboste Alb 2017, Château Purcari Alb de Purcari 2017, Fautor Illustro Chardonnay Sauvignon Blanc Rhein Riesling 2016

Recommended red wines: Minis Terrios Negru Împărat 2016, Vinaria Nobila Cabernet Sauvignon 2014, Castel Mimi Merlot Reserve 2012 & Cabernet Sauvignon Reserve 2012, Château Vartely Taraboste Roșu 2015, Mileștii Mici Codru 2009, Fautor Illustro Merlot Cabernet Sauvignon 2015, Equinox Echinoctus 2015, Chateau Cristi Cabernet Sauvignon Old Vines 2016

Moldova shares a long history with next-door Romania. As such, both Romanian-speaking countries also share a number of native varieties. These grapes, both in blends and as varietal wines, produce the most memorable wines of Moldova.

The important local red grapes are Fetească Neagră and Rara Neagră (known as Băbească Neagră in Romania). The important white counterparts are Alb de Onițcani, Fetească Albă, Fetească Regală, Plavai, and Viorica.

Eastern European grapes like Bastardo Magarachsky, Rkatsiteli and Saperavi are also cultivated. Despite Saperavi’s Georgian origin, it thrives exceptionally well in Moldova and makes a formidable backbone for the most profound Moldovan red blends. The best dry red Moldovan wines we tasted were made from either Moldovan varieties, Georgian varieties, or both.

Recommended white wines: Novak Alb de Onitcani 2017, ATÚ Viorica 2018, Cricova Crisecco NV, Château Vartely Fetească Regală 2018, Salcuta Winemaker’s Way Alb de Onitcani 2018, Kazayak Viorica 2018

Recommended red wines: Minis Terrios Roșu Împărat 2015, Carpe Diem Bad Boys 2016, Vinaria Nobila Fetească Neagră 2014, ATÚ Calibru 2017, Château Vartely Individo Rara Neagra 2017 & Individo Saperavi 2017, Mileștii Mici Negru de Mileștii 1987, Salcuta Eno Reserva 2015, Château Purcari Negru de Purcari 2015 & Roșu de Purcari 2015, Fautor Negre 2016, Gitana Lupi Rezerva 2015, Gogu Metafora 2017

The first Moldovan wine that awed us was an icewine made from Riesling. During our visit to Moldova, we were thrilled to learn that that wine wasn’t a fluke.

There are many exceptional botrytized sweet wines and icewines made in all three Moldovan wine regions. Icewine can be made in Moldova nearly every year as winter usually dips below -7 degrees Celsius. What further strengthens this ‘Moldovan sweet spot’ is different varieties are used to make sweet wines, including Muscat Ottonel, Traminer (Gewürtztraminer), Chardonnay, Rkatsiteli, Riesling, and even Cabernet Sauvignon.

Recommended sweet wines: Asconi Rosé Icewine Cabernet Sauvignon 2017, Castel Mimi Late Harvest Rkatsiteli 2013, Château Vartely Chardonnay dulce alb 2013, Mileștii Mici Margaritar 2005, Fautor Ice Wine Traminer Muscat Ottonel 2016, Ialoveni Reserva Pelicular 1995

Moldova, along with Armenia, was renowned for its grape brandy production in the Soviet states. Back then, those brandies were called Cognac. However, since 1909, only grape brandy produced in the Cognac region in France is legally allowed to be labeled as Cognac. As a result, Moldovan grape brandy needed to be renamed and rebranded if it wanted a share of the international market in the post-Soviet era.

Like Cognac, today, Divin bears PGI. With a tradition of over 100 years in Moldova, Divin is produced by double-distilling grape-based alcohol and aging it for at least three years in oak barrels. Depending on the length of maturation, Divin offers a range of scents and tastes: from flowers and spices, to caramel and tobacco. The best Divin, like Cognac, is smooth on the palate and balanced in taste, with a plethora of flavors that persist through a long finish.

An entry-level Divin, in a half-liter bottle, usually retails for less than five euros. For a respectable Divin, aged for 10 years and likely to appeal to experienced Cognac drinkers, expect to pay between 15 and 20 euros. For a truly hedonistic Divin that has been aged for 20 years, the price goes up to 80 euros and above. The step-up is boundless; 50 Year Old Divin exists too.

Today, the wine industry accounts for 2% of Moldova’s Gross Domestic Product and 6% of the country’s total exports, and Moldovan wines are available in over 50 countries around the world. These numbers speak for themselves: while success is always a work in progress, the Moldovan wine industry has clearly moved from an unhealthy reliance on one country to a robust export portfolio.

However, other challenges remain, including selling more wines at higher prices, rebranding Moldova as a quality wine-producing country, increasing domestic consumption, upgrading infrastructures and the service sector to boost the overall value chain, and valorizing the cultural significance of Moldovan wine. The need to tackle these challenges is, however, well-timed as a new generation of internationally educated winemakers and cosmopolitan minds are ready to step up and lead in this time of change.

Mihaela Sirbu, who studied hotel management in Switzerland and worked in the tourism sector in Abu Dhabi, joined her family business at Asconi Winery in 2017. “With my international background in hospitality, I hope we will be able to showcase the most authentic Moldovan traditions while following the latest wine tourism trends,” she said.

Sirbu is now in charge of tourism development at the winery, while her brother takes care of the vineyards. Her father, the founder of Asconi Winery, continues to oversee the entire operation of the estate, which includes wine production, two restaurants, and 20 rooms for guests. With the wide offering at the estate, the family team aims to attract more people, both local and foreign, to experience Moldova’s culture through wine.

The Asconi Winery, with more than 500 hectares of estate vineyards, is one of the largest private wineries in Moldova and one of the many case studies on how wine and entrepreneurship can be a core lever for nation-building in Moldova.

“During Soviet times, we did not have family-owned wineries at all, only state-owned, mega-wineries with hundreds and thousands of hectares,” said Ion Luca, former president of the Moldovan Small Wine Producers Association, winemaker-proprietor of Carpe Diem Winery and owner of Carpe Diem Wine Shop & Bar.

Luca was the first president of the Moldovan Small Wine Producers Association, which was established in 2008. To be a member of the association, a producer must have less than 20 hectares of vineyards and an annual production of no more than 100,000 liters.

Describing the members of Moldovan Small Wine Producers Association, Luca said, “We are a group of people who started from scratch in a boutique winery style, and we’re making limited quantities of wine. In order to place our wine on local and international markets, we have to unite in an association so that we can share efforts in promoting our wines on local and international fairs, make events together, educate consumers together, and also lobby and advocate for the ‘small guys’.”

Small producers are often squeezed out of restaurants’ wine lists and shelf space because they do not have the financial resources to compete with big producers. To counter that, Luca established Carpe Diem Wine Shop & Bar in the center of Chișinău, where wines of the small producers are under one roof.

To drink Moldovan wine represents taking a stand for the country, supporting a revolution, championing resilience, promoting diversity in wine, and planting a future for the whole wine industry. A glass of Moldovan wine stands for how the human spirit prevails amid calamity. It means helping more Old World wine countries to re-emerge and rewrite modern wine history.

Wine may simply be a beverage, but it can also be symbolic. If there are two overriding considerations we would employ when buying wine, they are: “Are we supporting something that we should be supporting?” and “Are we doing our part to promote diversity in the wine world?”

Moldova may be a small corner of the wine world, but it has the capability to show us something new that we don’t already know about wine. That’s if we give Moldovan wine a chance today.